This week we continue our multi-part series on the many facets of the global 30 x 30 conservation efforts as they continue across the state of California as just one example of local, state, and national efforts aggregated. We're in conversation with Jun Bando, the new executive director of the California Native Plant Society, and back in conversation with Liv O’Keefe, the senior director of Public Affairs for the Society. CNPS is an important agency in a larger coalition of agencies and groups contributing to California’s planning, assessment, and projects meeting the goals of 30 x 30 in this one large biodiverse state. A good portion of this broader coalition took part in CNPS’s 2022 conservation conference, entitled Rooting together: restoring connections to plants, place, and people, at which one whole learning track was dedicated to conservation via the 30 x 30 framework and funding as we look ahead.

Follow California's 30 x 30 efforts online through www.californianature.ca.gov/;

and the Federal level efforts at: www.doi.gov/priorities/america-the-beautiful

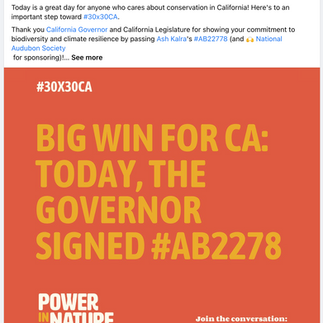

Follow California's Consortium of 30 x 30 partners: www.powerinnature.org/about/

For more on the CNPS 2022 Conservation Conference: https://conference.cnps.org/program/keynote-speakers/

For an in depth recap of the CNPS 2022 Conservation Conference by CNPS member and plantsman Doug Mandel as posted in the Shasta Chapter's Firecracker Newsletter: https://shasta-cnps.org/cnps-2022-conference-october-20-22/

IF YOU LIKE THIS PROGAM,

you might also enjoy these Best of CP programs in our archive:

JOIN US again next week, we continue our multi-part series devoted to conserving biodiversity and natural habitats in conversation with Yurok tribal member Brook Thompson and Forest Service botanist Joshua Chenoweth who are collaborating on the Yurok Tribe’s revegetation plan for the sacred Klamath River in its soon to be undammed life. Listen in.

Speaking of Plants and Place.....

...of biodiversity and habitat protection – this week we sing the praises of the sycamore. Now full transparency, I was all set to move to discussing a shrubby flowering plant genus – the Ribes – this week, but so many people commented on the habitat value and beauty this time of year of our native sycamores, that I will regale the ribes next week. The sycamores have the spotlight this week – and indeed this winter season across North America – and throughout the natural and cultivated ranges of sycamore. Who among us that recognizes the mottled spectral white and gray of the sycamore’s bark does not marvel at their almost glowing and often towering trunks in the spare winter days – naturally occurring in wet areas (like last week’s alders), but with some of their relatives used as beloved street trees around the world.

Sycamores are formally of the genus Platanus, the only genus in Platanaceae or plane tree family, there are somewhere around 8 species plus hybrids including Platanus Orientalis, the Oriental plane tree, Platanus Occidentalis, also known as the American sycamore, Platanus wrightii, which many call the Arizona sycamore, native to the Southwest and northern Mexico, and may be a hybrid of Platanus racemosa, the sycamore native my region. Also known as Aliso and as the Western or California sycamore, Platanus racemosa grows throughout much of California and down into Baja California, occurring naturally in canyons, floodplains, and along streams in several types of habitat, but is also used as a landscape tree across the west and pacific northwest.

This large tree commonly grows to 75 feet tall and 50 feet wide, but can grow to over 100 feet tall, with a trunk diameter of up to 3 feet. The stately trunks of these trees can be a single leader or divided into two or more large trunks splitting into many branches. And it is the bark of these trunks that catches the attention and holds the imagination – described as brown in the trees’ youth, and at the bases of even mature trees, as they grow the older areas of the trunk and branches are mottled with older darker bark peeling away to reveal large areas of luminous white young bark, interspersed with mid-aged pale gray to pinkish bark. The large lobed leaves are deciduous and can be extremely large, up to 10 in. wide. They age from bright pale green in spring to yellow and orangish brown in the fall. The remarkably inconspicuous flowers once pollinated become bumpy pom-pom like globes of many individual seeds. Western sycamore are tough plants, withstanding heat and wind and drought and they are fairly easy to grow with access to water – especially as they getting established.

Platanus x acerifolia known as the London plane is a hybrid dating back to the 1600s between the Oriental and the American sycamore and can be found as a street tree from London to Chicago and Los Angeles and so on, because of its striking trunk and its resilience to urban pollution in part based on their peeling bark, which sloughs off annual air pollution residue.

Some people find sycamores a little messy with their peeling bark, dropping fibrous seed balls, and their tendency to defoliate with summer wet as they are susceptible to the fungal disease anthracnose. But, under the right conditions, sycamores can live up to 2 or 300 years, with the oldest specimens being closer to 600 years old. And with that kind of age range, these trees have supported humans and wildlife for thousands of years. Again according to Calscape, sycamores are great small animal (like squirrel) bird, butterfly and caterpillar trees – Platanus racemosa having at least 8 butterfly larva associations.

A funny tree-friend life-supporting habitat story for you. While many of us remember important trees of our childhoods, many of us can also share tree friends we have made or found in our adulthood.

When I was pregnant with my second daughter, my then-husband and I were living in Bristol, England while he attended a fellowship program. We lived in a flat down a longish winding hill from the hospital where we would deliver our girl with the help of the midwives there. It was a warm lateish summer night – after midnight – when we knew it was time to make our way to the ward. We’d been in labor for several hours and the contractions were coming pretty quickly. And for anyone who has ever been in labor you will understand what I mean when I say, they were also coming on pretty loudly.

When we moved into our flat, we’d been happy to think we could just walk to the hospital when it was time. And so it was. It was a densely arranged residential street mostly made up of old brownstones that had been divided into many small apartments, like ours. It was a particularly livable street due to the large old trees that lined it – their large leave canopies taking the edge off heat, off the noise of traffic, and the many people. Offering limbs and cavities for birds to rest, to forage, to nest. I had always admired these trees – their gracious sheltering limbs as I made my pregnant way that summer, often hectically shepherding my eldest – just under 18 months at the time. But that night of my second daughter’s birth, as we made our slow and halting way up the long dark hill, I admired these trees with much greater intimacy and detail.

Street lamplight pooled between the massive evenly spaced trees, and every other tree or so supported me as I leaned into its steadiness – the cloud-like grey and white surface strong, and smooth, and cool to the touch of my hands and forehead. These trees each in turn literally breathed me through clenched teeth contractions the whole ½ mile to the hospital ward. They were our first loving midwives and doulas that night. When we moved to our first neighborhood in California 6 years later, I like to think my daughters and I all recognized the California sycamores lining the street there as both familiar friends and faraway relations of those London plane trees that July night in England.

I will always be grateful for the beauty of that luminous patterned bark seen supportively very close up.

Thinking out loud this week:

Last week we learned more about 30 x 30 and the California 30 x 30 plan, but did you know most state’s have their own 30 x 30 plan ready and available for download for you to know more and perhaps participate more wherever you are! My youngest sister sent Colorado’s Pathways to 30 x 30 report.

Send me a link to your state’s and I will share it forward with others in next week’s episode notes! (yes, I know I can find them myself - but the point is for YOU to find yours ;)

There’s always more to learn and there’s always even a little more we can do and grow…

There are two great take away ideas from this week's conversation I am turning in my brain and thinking about from my garden-level view – the first one being a point made by Jun that biodiversity loss and climate catastrophe go hand in hand – with the inverse also being true – the more biodiversity we protect and support, the greater the resilience to climate disruption. It might seem sort of intuitive, but it’s also in my mind worth remembering and holding onto as we garden for biodiversity – and the beauty of that.

The other is the note Liv made about that statement made by Native Communities advocate Rose Hammond of the Redbud Resource Group on the importance of sharing on and forward knowledge that’s been shared with openly with us – it’s the very best kind of insurance and education policy.

And just think how much knowledge every plant you’ve ever known has shared openly with you?

WAYS TO SUPPORT CULTIVATING PLACE

SHARE the podcast with friends: If you enjoy these conversations about these things we love and which connect us, please share them forward with others. Thank you in advance!

RATE the podcast on iTunes: Or wherever you get your podcast feed: Please submit a ranking and a review of the program on Itunes! To do so follow this link: iTunes Review and Rate (once there, click View In Itunes and go to Ratings and Reviews)

DONATE: Cultivating Place is a listener-supported co-production of North State Public Radio. To make your listener contribution – please click the donate button below. Thank you in advance for your help making these valuable conversations grow.

Or, make checks payable to: Jennifer Jewell - Cultivating Place

and mail to: Cultivating Place

PO Box 37

Durham, CA 95938

Comments